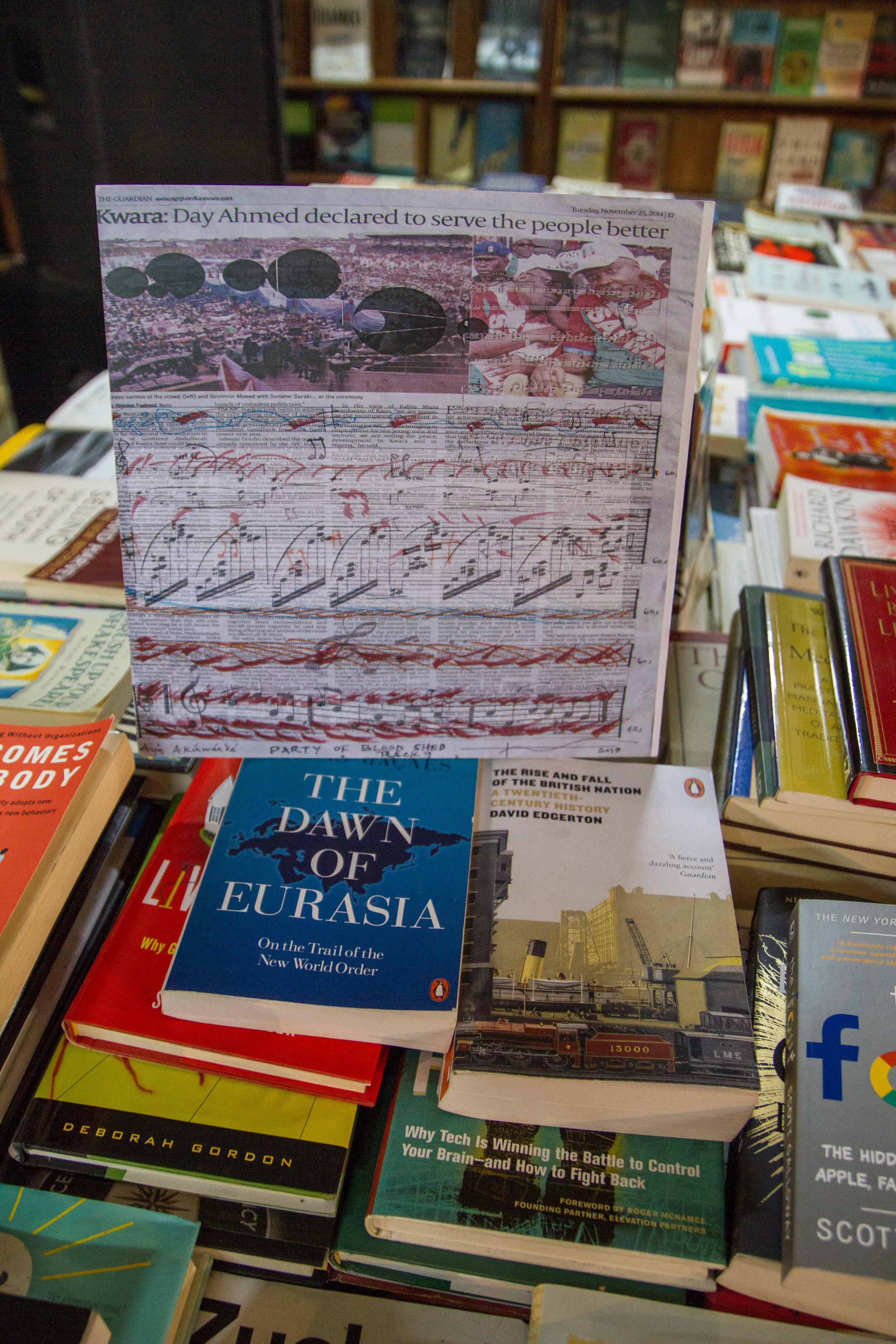

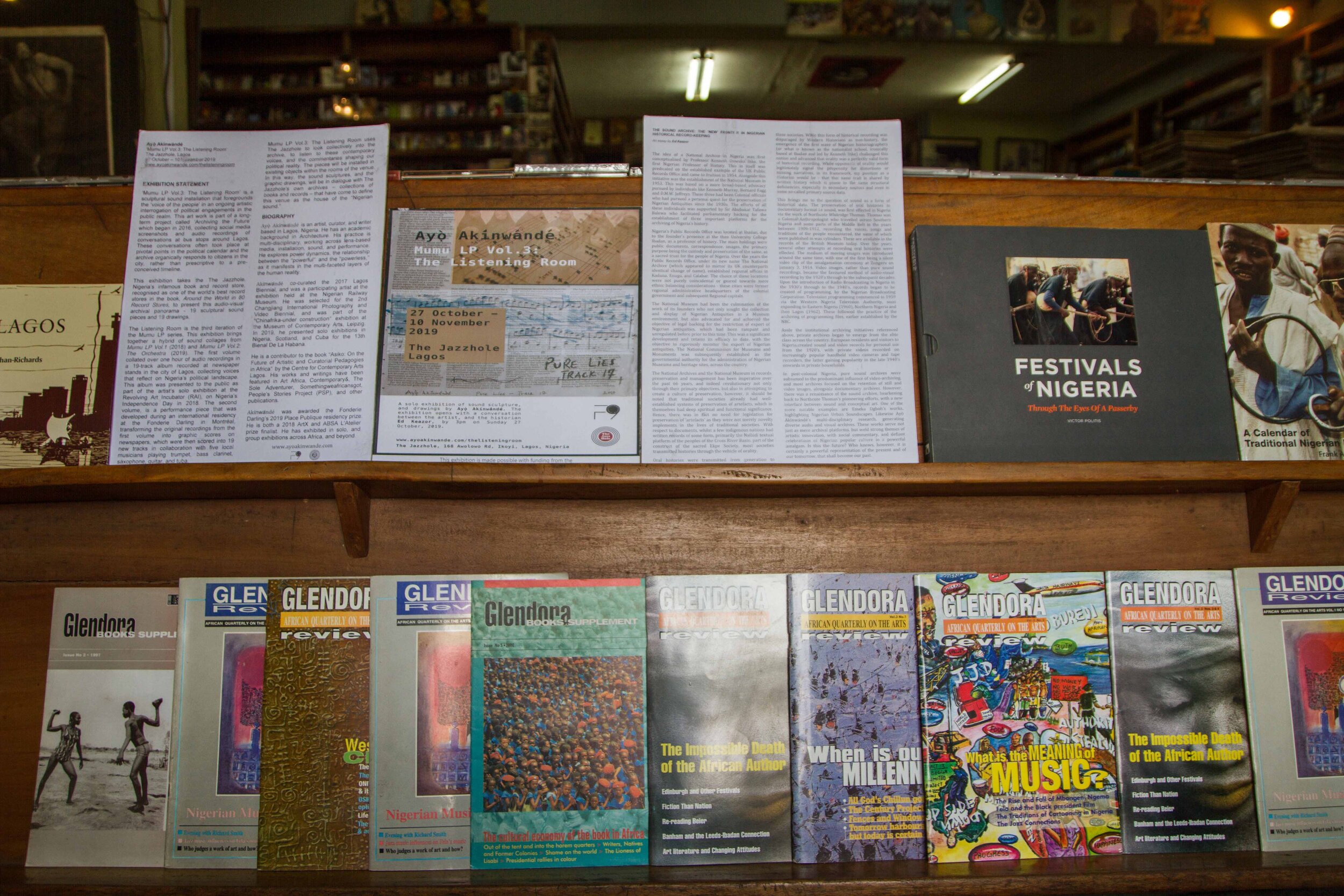

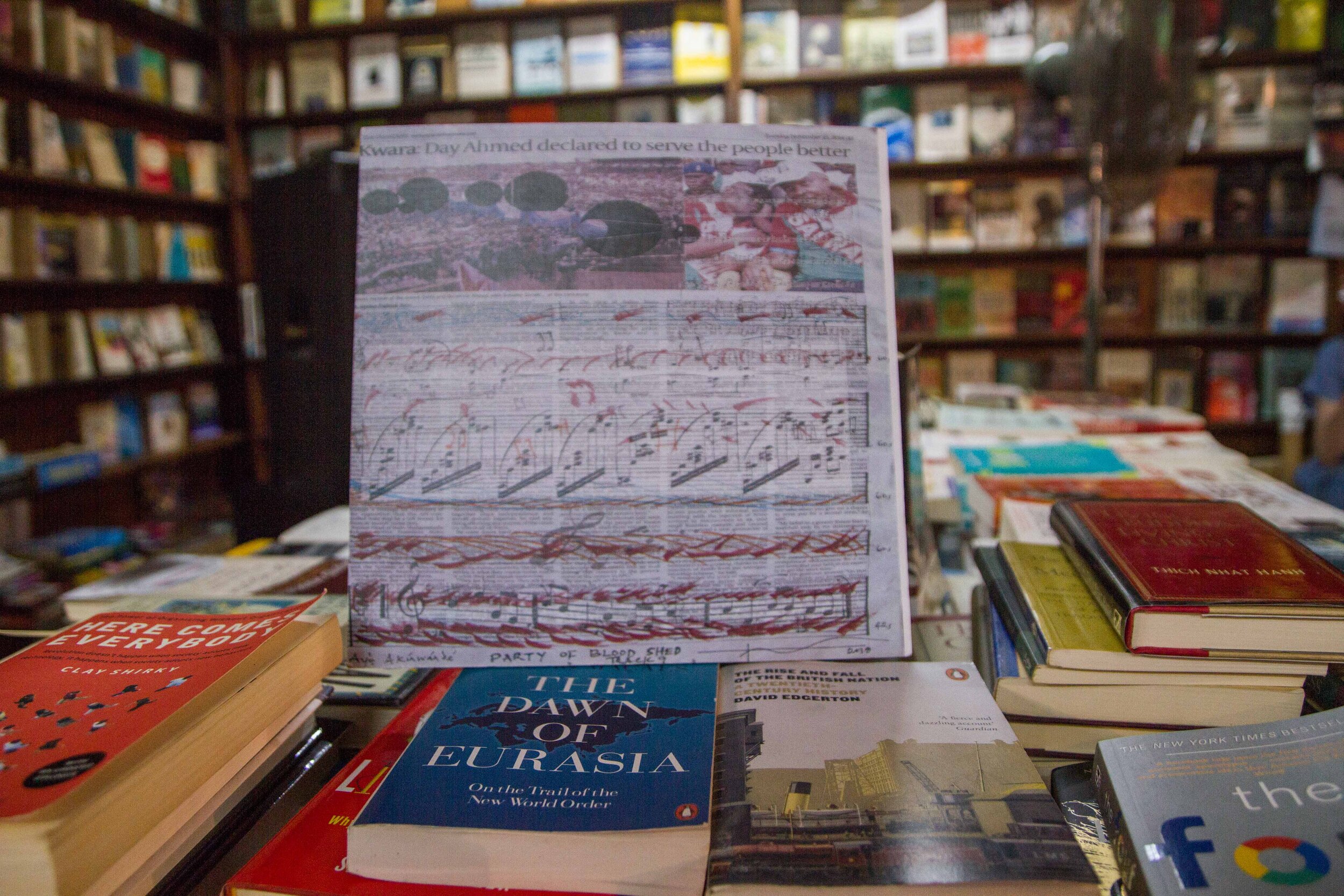

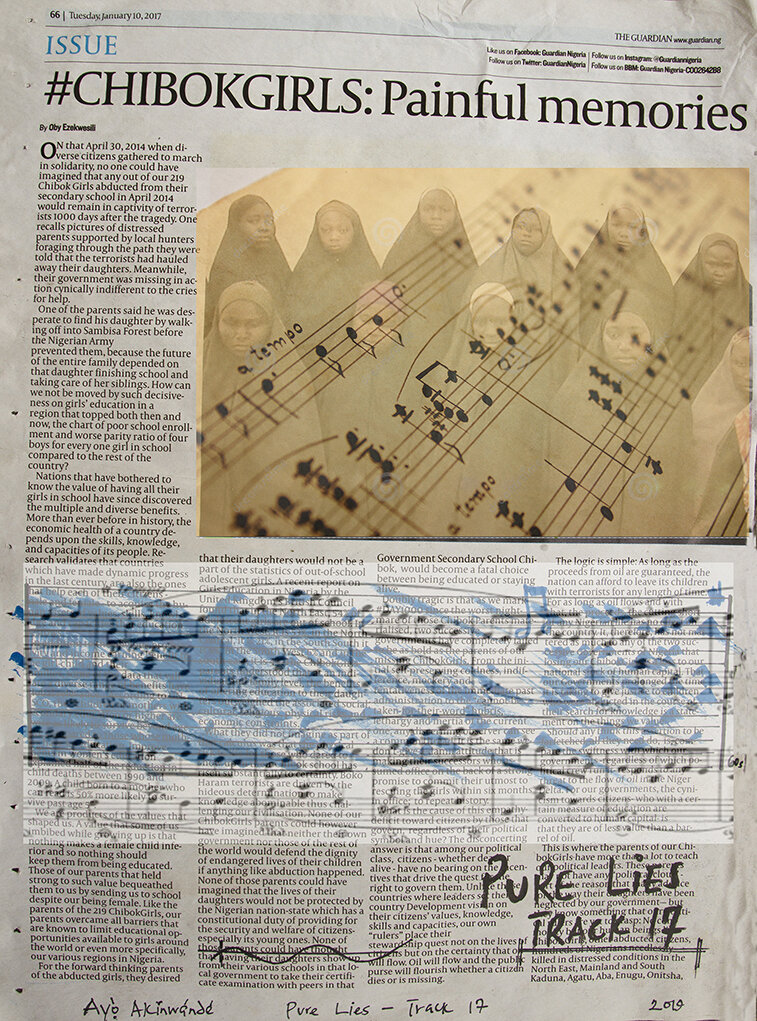

Ayọ̀ Akínwándé

’Mumu LP Vol.3: The Listening Room’

The Jazzhole, Lagos (Nigeria) 27 October – 10 November 2019

The Little Theatre Club, Mombasa (Kenya) 20 - 23 November 2019

‘Mumu LP Vol.3: The Listening Room’ is a sculptural sound installation that foregrounds the ‘voice of the people’ in an ongoing artistic interrogation of political engagements in the public realm. This art work is part of a long-term project called ‘Archiving the Future’ which began in 2016, collecting social media screenshots and audio recordings of conversations at bus stops around Lagos. These conversations often took place at pivotal points in the political calendar and the archive organically responds to citizens in the city, rather than prescriptive to a pre-conceived timeline.

This exhibition takes The Little Theatre Club and The Jazzhole, Nigeria’s infamous book and record store, recognised as one of the world’s best record stores in the book, Around the World in 80 Record Stores, to present this audio-visual archival panorama - 19 sculptural sound pieces and 19 drawings.

The Listening Room is the third iteration of the Mumu LP series. This exhibition brings together a hybrid of sound collages from Mumu LP Vol.1 (2018) and Mumu LP Vol.2: The Orchestra (2019). The first volume collated over one hour of audio recordings in a 19-track album recorded at newspaper stands in the city of Lagos, collecting voices that reflect on Nigeria’s political landscape. This album was presented to the public as part of the artist’s solo exhibition at the Revolving Art Incubator (RAI), on Nigeria’s independence day in 2018. The second volume, is a performance piece that was developed during an international residency at the Fonderie Darling in Montréal, transforming the original recordings from the first volume into graphic scores on newspapers, which were then scored into 19 new tracks in collaboration with five local musicians playing trumpet, bass clarinet, saxophone, guitar, and tuba.

Mumu LP Vol.3: The Listening Room uses The Little Theatre Club and The Jazzhole to look collectively into the archive, to listen to these contemporary voices, and the commentaries shaping our political reality. The pieces will be installed in existing objects within the rooms of the venue. In this way, the sound sculptures, and the graphic drawings, will be in dialogue with The Jazzhole’s own archives – collections of books and records – that have come to define this venue as the house of the “Nigerian sound.”

The Sound Archive: The ‘New’ Frontier in Nigerian Historical Record-Keeping

An essay by Ed Keazor

emergence of the first wave of Nigerian historiographers (or what is known as the nationalist school, ironically based at Ibadan and led by Kenneth Dike) challenged this notion and advanced that orality was a perfectly valid form of historical recording. While opponents of orality would legitimately signal the propensity for distortions or missing narratives, in its framework, my position as a Historian would be - that this same trait is shared by written history which is prone to the same structural deficiencies, especially in secondary sources and even in some so-called primary source data.

This brings me to the question of sound as a form of historical data. The preservation of oral histories in documentary format i.e sound, was first effected in Nigeria via the work of Northcote Whitridge Thomas. Thomas was a Colonial Anthropologist who travelled across Southern Nigeria and some parts of the Middle Belt in the years between 1909-1912, recording the voices, songs and traditions of the people encountered, the same of which were published in wax cylinders. These are available in the records of the British Museum today. Over the years, several other attempts at recording oral histories were effected. The medium of moving images was introduced around the same time, with one of the first being a silent video clip of the amalgamation ceremony at Zungeru on January 3, 1914. Video images, rather than pure sound recordings, became the favoured method of audio-visual recording by the 1920’s through to the subsequent decades. Upon the introduction of Radio Broadcasting in Nigeria in the 1930’s through to the 1940’s, records began to be created of programming, by the Nigerian Broadcasting Corporation. Television programming commenced in 1959 via the Western Nigeria Television Authority, soon expanding to Eastern Nigeria (1960), Northern Nigeria and then Lagos (1962). These followed the practice of the archiving of programming files, earlier established by the NBC.

Aside the institutional archiving initiatives referenced above, private archives began to emerge from the elite class across the country. European residents and visitors to Nigeria,created sound and video records for personal use from the 1920’s, with private videos recorded on increasingly popular handheld video cameras and tape recorders, the latter gaining popularity in the late 1940’s onwards in private households.

In post-colonial Nigeria, pure sound archives were subsumed to the predominant influence of video-archiving, and most archives focused on the retention of still and video images, alongside documentary archives. However, there was a renaissance of the sound archive, hearkening back to Northcote Thomas’s pioneering efforts, with a new interface between sound and conceptual art. One of the more notable examples are Emeka Ogboh’s works, highlighting Nigerian Urban Soundscapes. Likewise Ayọ̀ Akínwándé’s multi-disciplinary research, generating diverse audio and visual archives. These works serve not just as mere archival platforms, but weld strong themes of artistic innovation, with social commentary, and defiant celebrations of Nigerian popular culture in a powerful amalgam. Is this the future? Who knows, however, it is certainly a powerful representation of the present and of our tomorrow, that shall become our past.

The idea of a National Archive in Nigeria was first conceptualised by Professor Kenneth Onwuka Dike, the first Nigerian Professor of History. This in itself was predicated on the established example of the UK Public Records Office and came to fruition in 1954. Alongside this initiative was the establishment of the National Museum in 1953. This was based on a more broad-based advocacy pursued by individuals like Kenneth Murray, Bernard Fagg and D.M.W. Jeffreys. These three had been Colonial officials who had pursued a personal quest for the preservation of Nigerian Antiquities since the 1930s. The efforts of all these individuals was supported by Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa who facilitated parliamentary backing for the establishment of three important platforms for the archiving of Nigeria’s history.

Nigeria’s Public Records Office was located at Ibadan, due to the founder’s presence at the then University College Ibadan, as a professor of history. The main holdings were public documents, correspondence, images, the primary purpose being the custody and preservation of the same, as a sacred trust for the people of Nigeria. Over the years the Public Records Office, under its new name The National Archive (which appeared to mirror its UK counterparts identical change of name), established regional offices in Kaduna, Enugu, and Calabar. The choice of these locations were not purely coincidental or geared towards mere ethnic balancing considerations - these cities were former regional administrative headquarters of the colonial government and subsequent Regional capitals.

The National Museum had been the culmination of the work of its founders who not only sought the collection and display of Nigerian Antiquities in a Museum environment, but also advocated for and achieved the objective of legal backing for the restriction of export of Nigerian antiquities, which had been rampant and unregulated before prior to this time. This was a significant development and retains its efficacy to date, with the objective to rigorously monitor the export of Nigerian antiquities. The National Commission for Museums and Monuments was subsequently established as the governmental authority for the administration of Nigerian Museums and heritage sites, across the country.

The National Archives and the National Museum in records preservation and management has been imperative over the past 66 years, and indeed revolutionary not only through their primary objectives, but also in attempting to create a culture of preservation, however, it should be noted that traditional societies already had well-established systems of preservation of artefacts, which in themselves had deep spiritual and functional significance. Hence, there was in fact no need for legislation for preservation of ‘artefacts’ as they were not merely novelty implements in the lives of traditional societies. With respect to documents, whilst a few indigenous nations had written records of some form, primarily the Nsibidi textual platform of the peoples of the Cross River Basin, part of the construct of the sacred Ekpe Society, most societies transmitted histories through the vehicle of orality.

Oral histories were transmitted from generation to generation and constituted the sacred national archive of these societies. While this form of historical recording was disparaged by Western Historians as non-history, the

This exhibition was made possible with funding from the F9 Contemporary Arts Foundation, and the generous support of The Jazzhole, Lagos.